|

| December 2014/January 2015 issue of CBS Watch! Magazine |

If you've paid a visit to the supermarket this month, you may have seen the latest issue of CBS Watch! magazine, which is devoted to the original Star Trek television series. As I indicated last weekend, although the magazine is filled with beautiful and rare photographs taken during the production of the series, the text often leaves something to be desired. Rather than write a more traditional review, I've decided to do a fact-check of some of the magazine's more bizarre claims, in the order that they appear in the magazine. The text of each claim is quoted as it appears in the magazine, not paraphrased.

Without further ado...

| Selections from Roddenberry's RIT lecture can be found on Inside Star Trek (1976) |

Verdict: False. Although it incorporates much of the footage from the first pilot, "The Menagerie, Parts I and II" was awarded the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1967, not Roddenberry's original pilot. Star Trek's only two-parter beat out "The Corbomite Maneuver" and "The Naked Time," which were also nominated, along with Francois Truffaut's adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 and Richard Fleischer's film, Fantastic Voyage.

| The impressive bridge set built for "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: Partly true. Although the first pilot was enormously expensive for television -- the final budget came in at $615,781.56 -- this number simply doesn't compare to the money being spent on contemporary A-pictures. Consider the costs of films like 1963's Cleopatra ($32 million), 1962's Mutiny on the Bounty ($19 million), and 1959's Ben-Hur ($15 million), the cost of producing television sets (even for an expensive show like Star Trek) just doesn't compare.

| Ricardo Montalban in "Space Seed" (1967) |

Verdict: False. Roddenberry's familiarity with science fiction before Star Trek is debatable, but he had written science fiction at least once prior to Star Trek. Roddenberry's script for “The Secret Weapon of 117,″ part of the anthology program Stage 7, first aired on March 6, 1956. Although the episode is not currently available for public viewing, it reportedly stars Ricardo Montalban "as one of a pair of aliens trying to assess whether or not Earth has the technology to retaliate against infiltration and invasion by their species" and was definitely science fiction.

| Leonard Nimoy as Spock in "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: Partly true. Although a few performers from the first pilot (Edward Madden, Jon Lormer, Robert Johnson, Majel Barrett, Janos Prohaska, and Malachi Throne) later appeared as different characters in subsequent episodes, Nimoy was the only actor to reprise his role from the first pilot in a subsequent episode. Although the character of Christopher Pike appears in "The Menagerie, Parts I and II," he's played in those episodes by Sean Kenney, not Jeffrey Hunter.

| Still from "Arena" (1967) |

Verdict: Partly true. Although Brown gets screen credit, Coon wrote "Arena" as an original teleplay. Credit was awarded to Brown only after de Forest Research pointed out numerous similarities to Brown's short story that could result in litigation against Desilu. Chalk it up to a case of cryptomnesia on Coon's part.

| Jeffrey Hunter in "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: Partly true. Although the story goes that Hunter turned down the second Star Trek pilot to focus on feature film roles, he continued to work in television thereafter, even going as far to star in another pilot (Journey into Fear) in 1965. Hunter was seriously injured during the filming of ¡Viva América! (1969), but his death actually happened several months later, when he fell at his home in Van Nuys and hit his head on a banister.

|

| Gene Roddenberry's original Star Trek pitch document (1964) |

Verdict: True. Roddenberry's original pitch document, available here, includes six one sentence story concepts and nineteen longer story ideas, a number of which became the basis of later episodes. "The Day Charlie Became God" was later developed into a teleplay by D.C. Fontana called "Charlie's Law," and produced as the first season episode "Charlie X."

| John Hoyt as Dr. Philip Boyce in "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: True. Although Boyce isn't identified by his nickname in any final dialogue, Roddenberry's aforementioned original pitch document from early 1964 identifies the doctor as, "Captain April's only real confidant, 'Bones' Boyce considers himself the only realist aboard, measures each new landing in terms of the annoyances it will personally create for him."

| Still from "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: False. Behind the scenes photos (which can be seen on birdofthegalaxy's fabulous flickr page, here and here) show that the exterior of Talos IV was actually built on a soundstage with a painted backdrop, which is pretty obvious in the episode itself. Pages 6-10 of Bob Justman's shooting schedule (available here) confirm these "exteriors" were actually shot on stage 16 at Culver Studios.

| Leonard Nimoy and Peter Duryea in "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: False. Dedicated fans know that the term "phaser" wasn't coined until after the first pilot was completed. Captain Pike and company carry "Laser pistols" according to the revised teleplay dated November 20, 1964, and dialogue in the complete episode refers to "hand lasers." The same caption also refers to Number One leading an "away team," a term which wouldn't be used until Star Trek: The Next Generation; Star Trek instead referred to "landing parties."

| Majel Barrett in "The Menagerie" (1964) |

Verdict: Probably false. Roddenberry often repeated this claim, which can be found in print in The Making of Star Trek (1968) and heard on Inside Star Trek (1976), but Herb Solow vehemently denied it in Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (1996) and elsewhere. Recalling NBC's response after the first pilot, Solow says the network told the production, "We support the concept of a woman in a strong, leading role, but we have serious doubts as to Majel Barrett's abilities to 'carry' the show as its costar" (Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, page 60).

| Still from "The Savage Curtain" (1969) |

Verdict: Partly true; partly unknown. Bar Refaeli did quote from the script to "The Savage Curtain" in a July 16, 2014 Twitter post, mistaking it for a genuine Abraham Lincoln quote. However, the teleplay to "The Savage Curtain" was written by Gene Roddenberry and Arthur Heinemann; without examining the various script drafts of the episode, it's hard to say if the quoted words were Roddenberry's alone, as the magazine claims.

|

| Lucille Ball |

Verdict: False. Ball was the head of Desilu, and in that position, instrumental in getting Star Trek made, but she was not in any useful sense of the word a "producer" on Star Trek. Also, according to Herb Solow, Ball had little to do with convincing NBC to order a second pilot. In Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, Solow recounts a meeting with Mort Werner, held soon after the NBC schedule was announced for the fall of 1965 (and Star Trek wasn't on it):

Mort, Grant [Tinker], and Jerry [Stanley] were still taken by what we'd accomplished. And Mort had a complaint: 'Herb, you guys gave us a problem.'

'Sorry, Mort, we tried our best.'

'That's the problem. I didn't think Desilu was capable of making Star Trek, so when we looked over the pilot stories you gave us, we chose the most complicated and most difficult of the bunch. We recognize now it wasn't necessarily a story that properly showcased Star Trek's series potential. So the reason the pilot didn't sell was my fault, not yours. You guys just did your job too well. And I screwed up.'

I shook my head in awe. No, no, this wasn't a network executive talking to me. This was the Good Witch of the East come to lay gold at our feet. I conjured up all my good thoughts. 'So let's do another pilot.'

'That's exactly why we're here. We'll agree on some mutual story and script approval, and then, if the scripts are good, we'll give you some more money for another pilot.'

-Herbert F. Solow, Inside Star Trek: The Real Story (1996), page 60It appears that this myth about Lucille Ball first originated in an online piece by Will Stape in 2007, and has been repeated in several other places online since, including this piece from blastr in 2013.

| Leonard Nimoy in an early Star Trek publicity photo (1964) |

Verdict: False. Nimoy's guest appearance on The Lieutenant, in an episode titled "In the Highest Tradition," first aired on February 29, 1964, and probably was filmed in late 1963. Roddenberry's written pitch for Star Trek wasn't completed until March 11, 1964, and he didn't have a meeting (or sign a deal) with Herb Solow at Desilu until April of 1964. Whenever Roddenberry began considering Nimoy for the part, he certainly wasn't starting to actually cast the series when Nimoy guest starred on The Lieutenant. Moreover, actor Gary Lockwood claims he's the one who suggested Nimoy for the part to Roddenberry, but only after The Lieutenant was off the air (the last episode of the series aired on April 18, 1964).

|

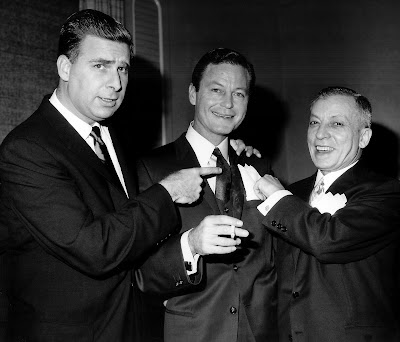

| Gene Roddenberry, DeForest Kelley, and Jake Ehrlich, Sr. (1960) |

Verdict: False. Gene Roddenberry never worked as a director in film or television, and he never wrote a pilot called Sam Benedict. Roddenberry did write a pilot in 1960 called 333 Montgomery, based on a book about famous lawyer Jake Ehrlich, which starred DeForest Kelley. Ehrlich's life later became the inspiration for the short-lived series Sam Benedict, which aired during the 1962-63 season, but that show didn't involve Roddenberry or Kelley. 333 Montgomery is currently available on YouTube in three parts: here, here, and here.

| Walter Koenig as Chekov in "Catspaw" (1967) |

Verdict: Contested. Roddenberry did write a letter to the editor of Pravda on October 10, 1967 in which he said, "about ten months ago one of the stars of our television show, STAR TREK, informed us he had heard that the youth edition of your newspaper had published an article regarding STAR TREK to the effect that the only nationality we were missing aboard our USS Enterprise was a Russian." Whether or not the editorial in the alleged youth-edition of Pravda actually existed remains an open question, but Roddenberry's letter suggests the story was more than a publicity stunt. More can be read about the issue at Snopes.

| Still from "Plato's Stepchildren" (1968) |

Verdict: False. This myth was pretty thoroughly debunked by The Agony Booth last month, and I offered some additional comments regarding the scene here.

| Still from "The Trouble with Tribbles" (1967) |

Verdict: False. The Klingons, established in season one's "Errand of Mercy," first re-appeared in season two's "Friday's Child," the third episode produced for the second season and the eleventh to air. The Klingons actually make their third appearance on Star Trek in "The Trouble with Tribbles," which was the fifteenth episode aired during season two, and the thirteenth produced. As for the first episode of the second season, "Amok Time" was the first episode to be aired in season two, and "Catspaw" was the first produced.

| Lawrence Montaigne in "Amok Time" (1967) |

Verdict: False. Although Desilu did have Montaigne at the ready in early 1967, in case contract negotiations with Nimoy for the second season fell through, there's no evidence that Montaigne was in the running for the role of Spock in 1964 and Nimoy never left Mission: Impossible for Star Trek. Indeed, Nimoy didn't appear on Mission: Impossible until after Star Trek was cancelled, when the actor joined the cast as Paris for two seasons from 1969 to 1971.

Special thanks to blog reader Neil B. for loaning me his copy of the magazine for review, and suggesting this article in the first place.

Select images courtesy of Trek Core.

Sources:

The Gene Roddenberry Star Trek Television Series Collection (1964-1969)

The Making of Star Trek (Stephen Whitfield and Gene Roddenberry, 1968)

CBS Watch! Magazine (December/January 2015)